Patient examination

1. Visual inspection

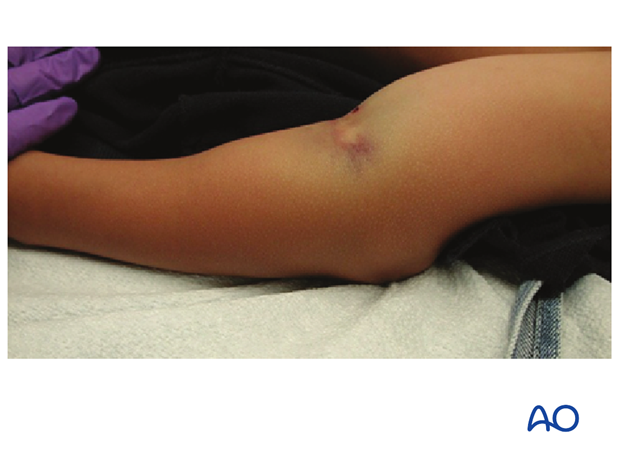

The patient is inspected visually for the following signs:

1. Deformity of the elbow region: Caution should be taken during further examination to avoid pain during eg, palpation

2. Skin discoloration: Indicative of severe fracture displacement and entrapment of muscle/soft tissues

3. Color of hand/fingers:

- Normal/red: Normal peripheral circulation

- Pink: Intact but reduced peripheral circulation

- White: Absent Peripheral circulation

See section on vascular injury below.

2. Palpation

Peripheral pulse is verified by palpation: see section below on vascular injuries.

3. Neurological assessment

Neurological damage can be caused either by the fracture, or following manipulation and fixation.

It is essential to perform a systematic neurological assessment both pre- and postoperatively and document the function of the individual peripheral nerves.

Neurological assessment can be very difficult to perform and is influenced by the level of pain and the age of the child.

In cases where the neurological compromise is caused by the fracture, exploration of the nerve is rarely necessary as it nearly always recovers.

Recovery may be slow and an interval of 4-6 months is recommended before exploration.

In cases where the neurological compromise could be caused by K-wire insertion, either through the medial epicondyle, or by penetration of a lateral wire, the K-wire should be removed promptly.

4. Vascular injuries

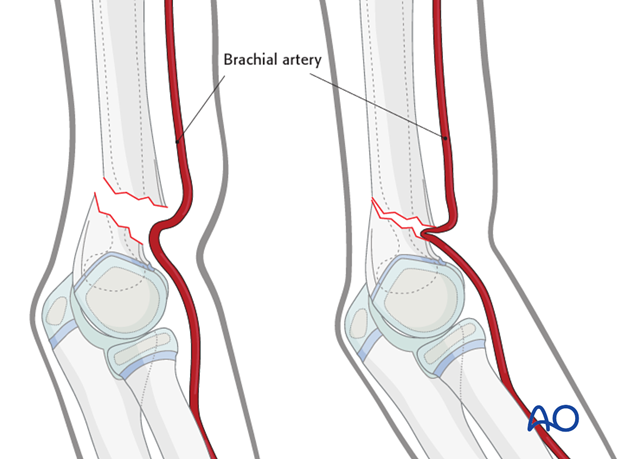

Extension type supracondylar fractures with marked displacement can injure the brachial artery, which lies just anterior to the distal humerus at the fracture site.

An absent radial pulse indicates vascular compromise, which may be due to kinking, or tethering, of an intact artery.

Alternatively, there may be an intimal tear, thrombosis, or complete transection of the artery.

Abundant collateral circulation may provide adequate distal perfusion, even with a complete tear of the brachial artery.

Collateral circulation is not always adequate to provide distal perfusion and the integrity and function of the limb may be at risk.

Peripheral radial pulse is verified by palpation:

- Normal pulse: No danger of vascular compromise, but does not exclude compartment syndrome

- Reduced pulse: Sign of vascular spasm or external compression

- Absent pulse: Entrapment of the vessel in the fracture, blocked by dislocated fragment, or ruptured vessel

Pre-reduction management options:

- Normal pulse, perfused hand: Fracture reduction and fixation

- Reduced pulse, perfused hand: Fracture reduction and fixation

- Absent pulse, perfused hand: Immediate fracture reduction followed by pulse and hand perfusion reassessment

- Absent pulse, nonperfused hand: Immediate fracture reduction followed by pulse and perfusion reassessment

Absent radial pulse with nonperfused hand

Limb ischemia in this context is a surgical emergency.

Consultation with a colleague capable of performing a small vessel repair should be immediately undertaken.

This may be a plastic surgeon, vascular surgeon, or general surgeon depending on local availability and training.

The child should be taken as a matter of urgency to the operating room.

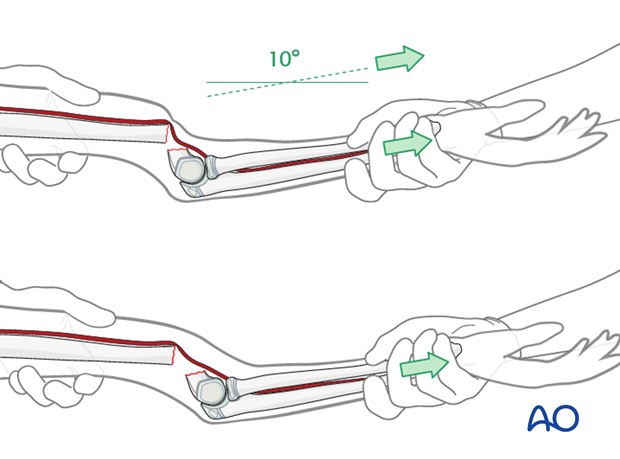

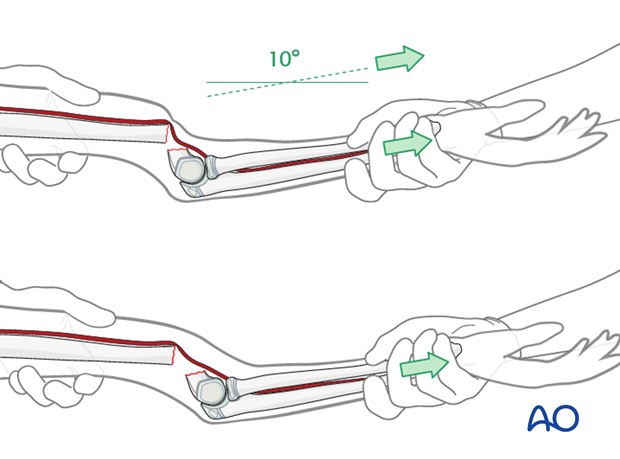

A closed reduction maneuver should be attempted initially and care must be taken not to stretch the already compromised artery: the traction should be gentle but sustained over 5-10 minutes.

If anatomical reduction can be obtained, the supracondylar fracture should be stabilized with intraosseous K-wires, or external fixator, and the vascular status reassessed.

Fracture reduction often leads to restoration of perfusion of the hand within 15-20 minutes.

In such cases, forearm compartment syndrome is a risk – see below.

Post-reduction management options:

- Circulation, pulse and perfusion return Definitive fracture fixation

- Perfusion returns but pulse not palpable (pulseless, pink hand): Definitive fracture fixation, followed by close monitoring of vascular status

- Pulse and perfusion do not return (pulseless, white hand): Exploration of the cubital vessels

- Arteriography is used in some cases, but as the site of arterial trauma is usually determined by the level of the fracture, this is not essential

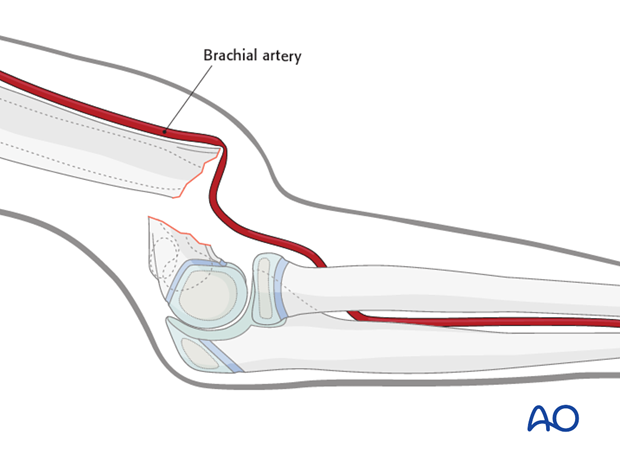

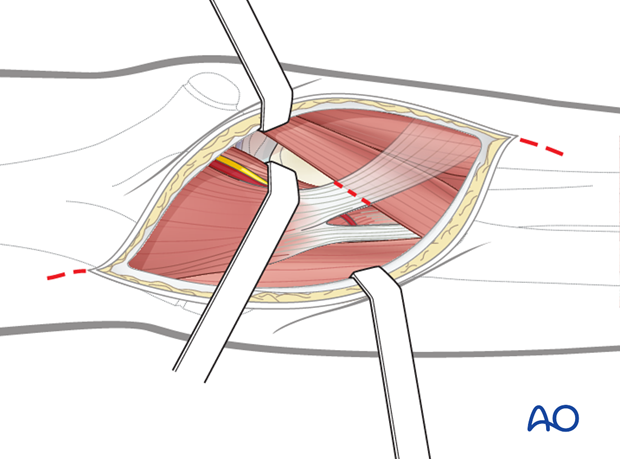

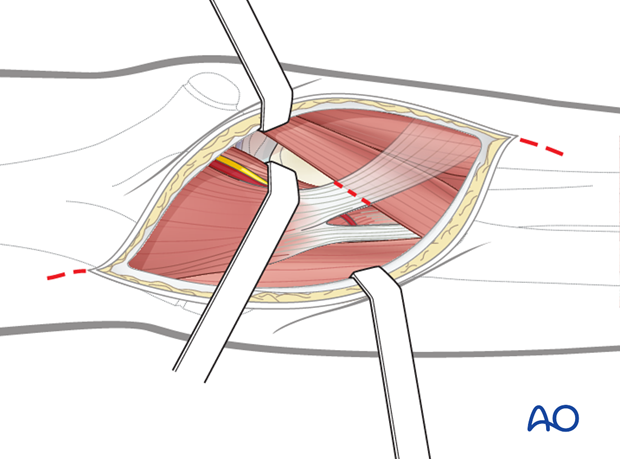

If the fracture cannot be reduced, an anterior approach to the antecubital fossa is performed. The brachial artery is often identified at the fracture site and exposure is improved by releasing the lacertus fibrosus.

The fracture is reduced under direct vision and stabilized with intraosseous K-wires. The vascular status is then reassessed.

Release of the vessel and reduction of the fracture often lead to restored perfusion of the hand. The radial pulse may, or may not, return. Skin color, temperature and capillary refill are the most important clinical assessments of vascularity. Doppler/ultrasound examination or pulse oximetry can be used as adjuncts to clinical assessment.

Decisions regarding arterial reconstruction are made jointly with the vascular consultant.

If the hand remains nonperfused, or poorly perfused, following anatomical reduction and fixation of the fracture, arterial reconstruction is usually required.

If good perfusion returns, the decision needs to be individualized and there is no consensus regarding the necessity for arterial reconstruction.

In such cases, forearm compartment syndrome is a risk – see below.

Absent radial pulse with adequately perfused hand

The child should be taken as a matter of urgency to the operating room. A closed reduction maneuver should be attempted initially, as already described.

If anatomical reduction can be obtained, the supracondylar fracture should be stabilized with intraosseous K-wires, or external fixator, and the vascular status reassessed.

Fracture reduction may lead to a restored radial pulse in which case no further treatment may be necessary.

In such cases, forearm compartment syndrome is a risk – see below.

If the fracture cannot be reduced, an anterior approach to the antecubital fossa is performed. The brachial artery is often identified at the fracture site and exposure is improved by releasing the lacertus fibrosus.

The fracture is reduced under direct vision and stabilized with intraosseous K-wires, or external fixator. The vascular status is then reassessed.

Release of the vessel and reduction of the fracture often lead to restoration of the radial pulse.

If perfusion of the hand is lost, following closed or open reduction, urgent consultation with a vascular surgical colleague is necessary.

If the radial pulse remains absent but the hand remains well-perfused, there is no consensus on the role of arterial reconstruction. The child may be treated with close observation.

Forearm compartment syndrome

Depending on the warm ischemia time, forearm compartment syndrome is an ever-present risk in supracondylar humeral fractures complicated by vascular compromise.

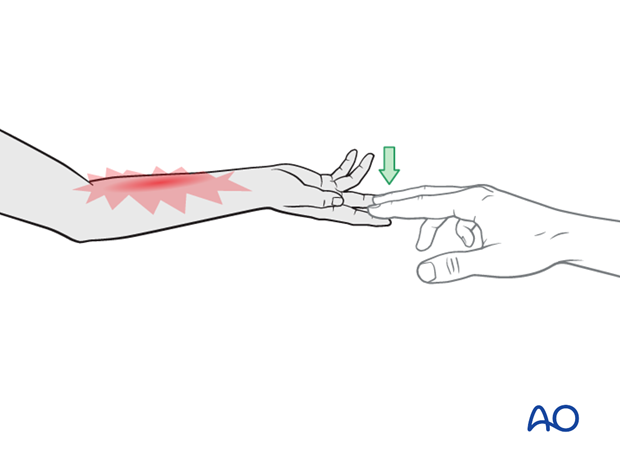

The most straightforward clinical test for evolving muscle ischemia is pain on passive digital extension and/or flexion.

Forearm compartment syndrome and fasciotomy are addressed in detail in the pediatric distal humerus section of AO Surgery Reference, to which the reader is referred.

5. X-ray examination of the distal humerus

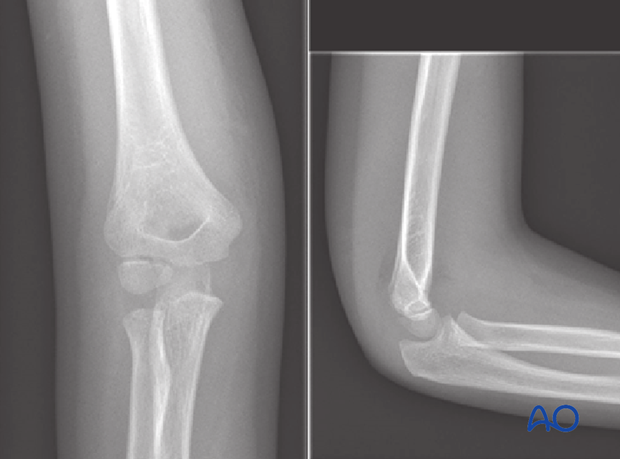

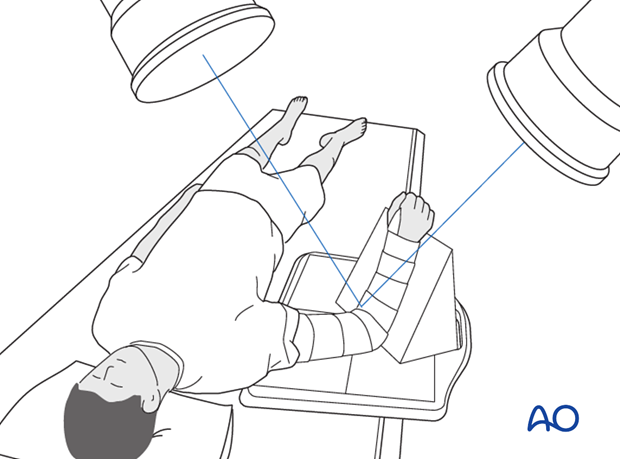

Standard, AP and lateral views are recorded for all distal humeral fractures.

The arm is often held in a splint so that the elbow cannot be extended and it is difficult to obtain standard AP views.

Tricks to obtaining two perpendicular views are described below.

If the fracture is clearly displaced and surgery is indicated, a second view may be postponed until the patient is under general anesthesia and images can be taken with the arm in traction.

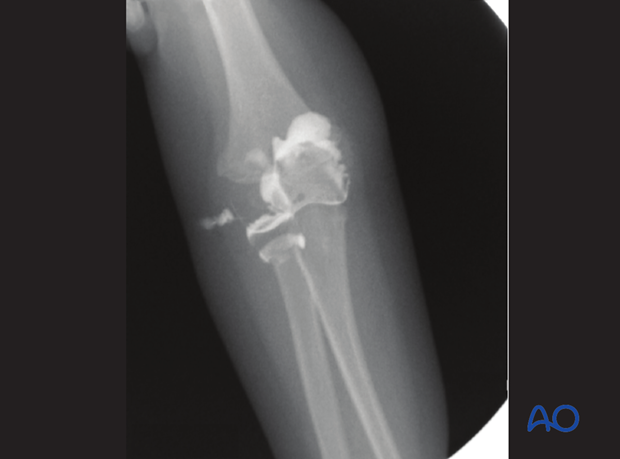

In the two images shown here, the fracture is so severely displaced that only one x-ray is necessary to determine the indication for intervention.

AP view

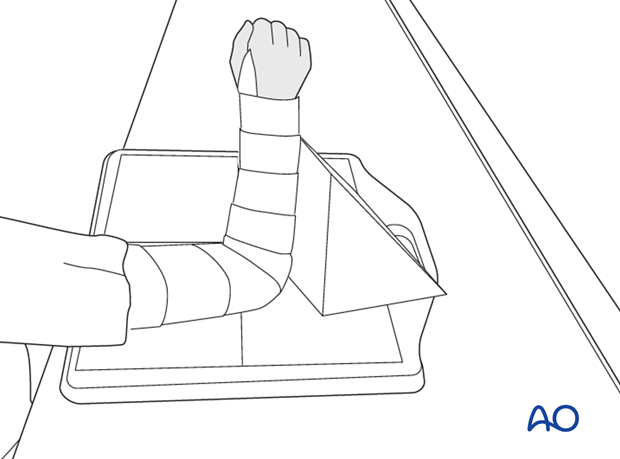

Due to pain, or preliminary fixation of the arm in a splint or cast, it is often difficult to extend the elbow.

To achieve good quality AP x-rays without causing unnecessary pain, the following two solutions can be used:

- Option 1: With the patient seated, the humerus is placed flat on the x-ray table, without moving the flexed elbow

- Option 2: If the patient cannot be positioned to allow the upper arm to lie flat on the table, the x-ray film cassette is tilted and the x-ray beam is directed perpendicular to the upper arm

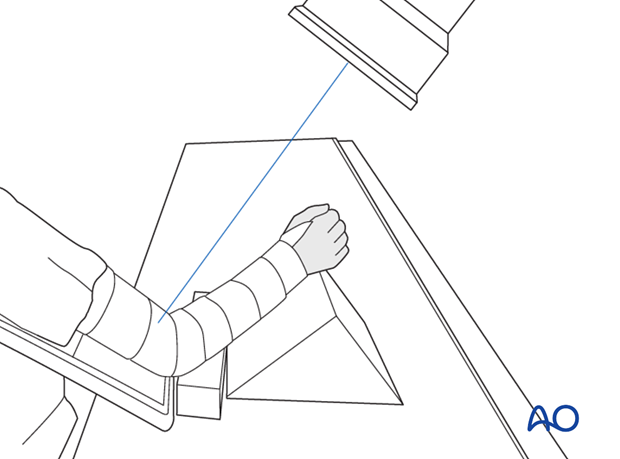

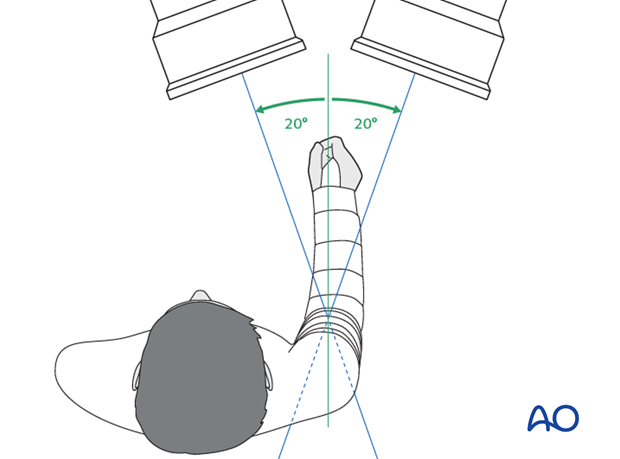

It has been demonstrated that the x-ray beam can be directed up to 20° off the long axis of the forearm, aiming at the distal humerus, without significant projectional distortion.

See: Dodge HS. Displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children--treatment by Dunlop's traction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972 Oct;54(7):1408-1418.

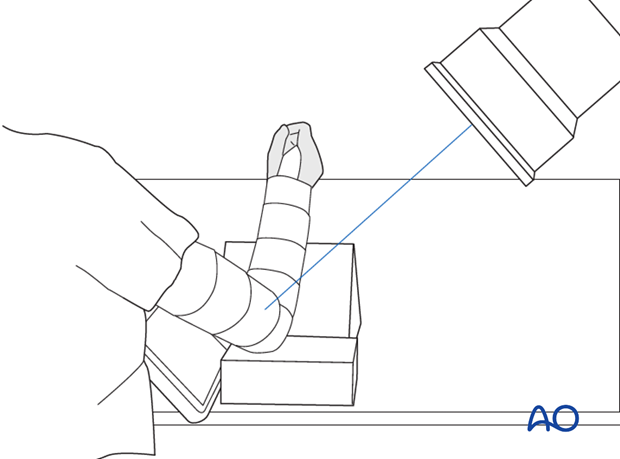

Lateral view

To reduce patient discomfort, the x-ray is taken by altering the position of the x-ray film cassette and the x-ray device, rather than attempting to rotate the arm.

Oblique views (internal and external)

If the fracture is not clearly visible in the AP and lateral views, 45° oblique views may be helpful, particularly for intraarticular lesions.

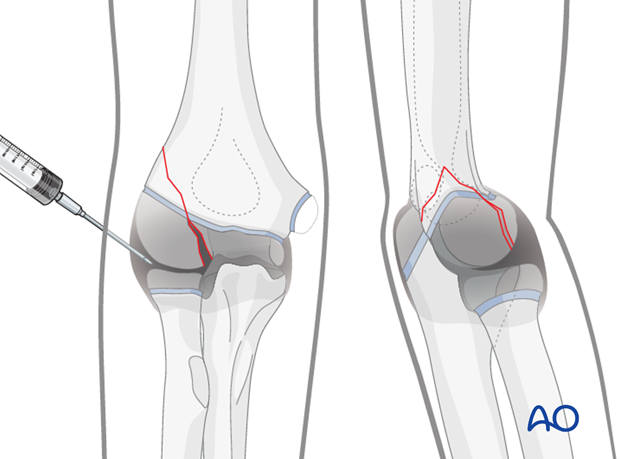

6. Arthrography (intraoperative)

Arthrography may also be used, particularly in younger children without secondary ossification centers.

This usually requires a general anesthetic in younger children, but can be undertaken under local anesthesia in older, compliant children.

Dynamic arthrography can also be helpful for diagnosis, especially if MRI or CT are unavailable.

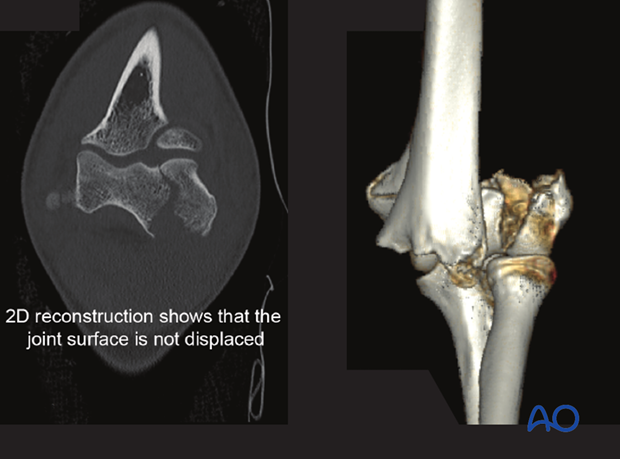

7. CT scan

CT scans may give additional information in the following situations:

- Discrepancy between clinical examination and clinical findings (e.g., large swelling without visible fracture on x-ray)

- Fracture pattern is unclear on x-ray

- Preoperative planning of complex intraarticular fractures

Note: 3D reconstruction will give surface information of the fracture. 2D reconstruction allows visualization of fracture lines within the bone.

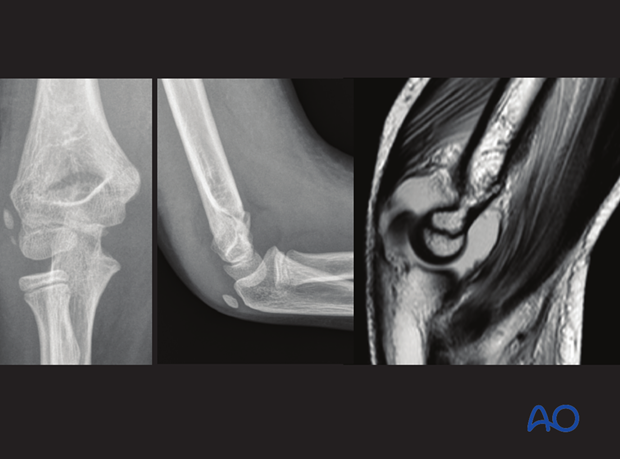

8. MRI

MRI is rarely indicated in acute trauma, due to the longer recording time and the need for sedation/anesthesia.

Relative indications include:

- Equivocal intraarticular fractures

- Persisting pain, despite negative x-ray and CT examination

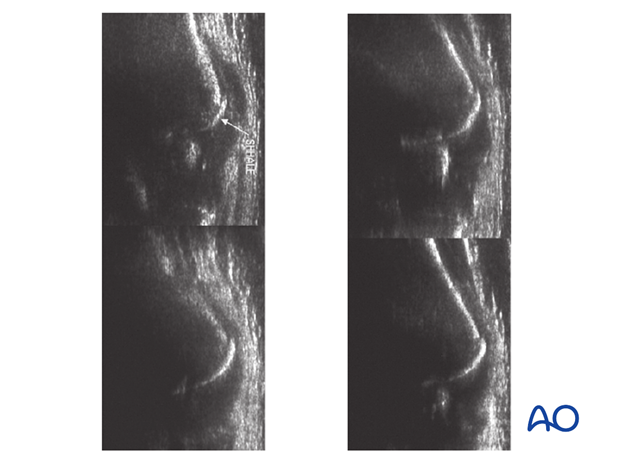

9. Ultrasonography

When intraarticular fractures are suspected, ultrasonography can help to identify complete or incomplete/hanging cartilaginous fractures.

This is particularly useful in young children with thick epiphyseal cartilage, especially in cases with a joint effusion.

This is an example of ultrasonography demonstrating a small osteochondral fragment of the anterior portion of the capitellum.